{Book Review: Nearby History: Exploring the Past Around You, by David E. Kyvig and Myron A. Marty, Published by Rowman & Littlefield}

Nearby History is called ‘a comprehensive handbook for those interested in investigating the history of communities, families, local institutions, and cultural artifacts.’ But it is much more than that. What I found this book to be is more like a guide, or assistant, that brings the family historian to the next level beyond family trees. It starts out by answering the question, Why Nearby History? And indeed, it provides a very solid answer that should matter to every family historian — if we are to write about the life of an ancestor, we need to consider that they ‘instinctively knew what had happened nearby, to himself, his ancestors, his neighbors, and other ordinary people, [that] had shaped their lives.’ Knowing about one’s ancestor is more about what impacted their lives from outside of themselves. We could write about what we ‘think’ our ancestor’s life was like, but most likely we are taking it from what we ourselves know. Even if we try to imagine without doing this type of investigation, we can fall short of their reality. As David and Myron state in this book, ‘History is an approach to understanding earlier times that seek to compensate for the imperfections of memory and myth.’ So, chapter 1 prepares us by helping us to understand why we need to do this. At the end of the chapter, references for further reading are provided.

Nearby History is called ‘a comprehensive handbook for those interested in investigating the history of communities, families, local institutions, and cultural artifacts.’ But it is much more than that. What I found this book to be is more like a guide, or assistant, that brings the family historian to the next level beyond family trees. It starts out by answering the question, Why Nearby History? And indeed, it provides a very solid answer that should matter to every family historian — if we are to write about the life of an ancestor, we need to consider that they ‘instinctively knew what had happened nearby, to himself, his ancestors, his neighbors, and other ordinary people, [that] had shaped their lives.’ Knowing about one’s ancestor is more about what impacted their lives from outside of themselves. We could write about what we ‘think’ our ancestor’s life was like, but most likely we are taking it from what we ourselves know. Even if we try to imagine without doing this type of investigation, we can fall short of their reality. As David and Myron state in this book, ‘History is an approach to understanding earlier times that seek to compensate for the imperfections of memory and myth.’ So, chapter 1 prepares us by helping us to understand why we need to do this. At the end of the chapter, references for further reading are provided.

Chapter two brings the project in order, helping us to focus on what can be explored. Most useful in this chapter are the 21 pages dedicated to questions to be asked about the family, places of residences, the neighborhood, organizations the family was involved in, the community, and even what they title ‘Functional Categories,’ which starts with the question under the topic, ‘Environmental Settings,’ — How has the natural situation, the atmosphere, air and water quality, climate, terrain, and presence or absence of natural resources changed over time? If writing about an ancestor in 18th century New York City, fresh water and sewage was a genuine concern that was different from today’s concerns about the same resources..

Chapter three brings the family historian into the realm of storytelling, explaining that there are different ways to tell stories. They explain that ‘good storytellers have a sense of their audience’s curiosity and interests.’ The chapter also introduces the term ‘traces,’ referring to the clues left behind that tell an ancestor’s story, finding them through the immaterial, material, written, and representational. The chapter brings the historian from simply writing to opening up a treasure box full of ways in which to communicate to bring the story into its fullness.

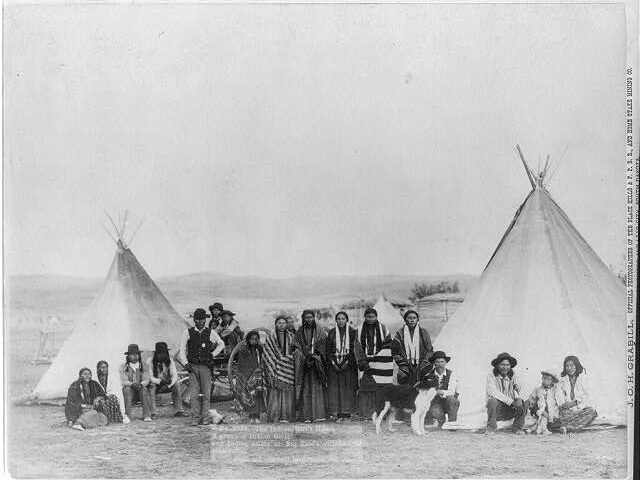

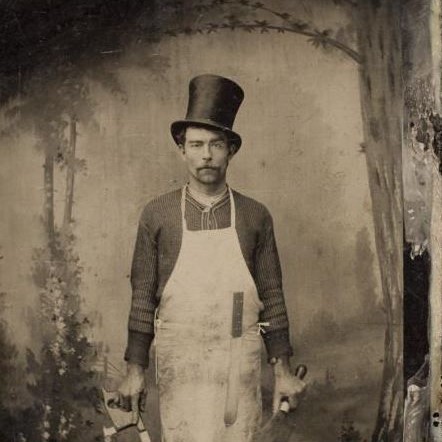

From this point, chapters four through nine take detailed time to help the reader discover how to find material with chapter headings: Published Documents, Unpublished Documents, Oral Documents, Visual Documents, Artifacts, as well as Landscapes and Buildings. As an example of how the authors provide a greater depth into the research to write the story, they give tools of how to examine documents, asking questions like whether they were firsthand knowledge, consider who the recorder was, if they were a neutral party, who was the document created for, what was the intention of the document’s use, was it created at the time of the event and whether the document was a replica or original. This is just a smattering of what the authors bring to the family history writer’s attention to consider when using a resource. In addition to lists of how to conduct an interview before, beginning, during, and after, in the Oral Documents chapter, the authors lay out a list of what can thwart a good interview. In Visual Documents, the authors provide concise instruction on how to read photographs, the limits of photographs, as well as how to preserve them, copyright issues, and also suggest considering motion pictures and videotapes on a smaller level. The chapter on Artifacts is not often found in books discussing family history writing. However, the information that is set out in the chapter is intriguing, including the section on museums and how they can be a view into the lives of our ancestors.

The book wraps up with three chapters: Preserving Material Traces; Research, Writing, and Leaving a Record; and, Linking the Particular and the Universal. Appendices include Forms to Request Information from Federal Agencies; Sample Gift Agreements; Sources of Archival Storage Products and Information; and, Using the World Wide Web in Nearby History.

CONCLUSION: This book is an essential addition to any family genealogist who is the recorder and keeper of ancestral history. It is a unique tool that is extremely comprehensive as a guide, providing uncommon resources and assistance in developing an extensive detailed story of family history to produce a solid account. The layout of the chapters are exceptional in its progressive form, leading the historian in a step-by-step course of action that can be taken in snippets. With each step acting as a mini project, it is conducive in bringing the goal of developing a family history easily to its intended objective, eliminating the feeling of being overwhelmed by the idea of the mission. Highly recommended.