{Buildings Archaeology Artifactual Feature Origins Part II — Trenched Timbers}

INTRODUCTION

The first technique covered in this series of artifactual features used in early American homes by immigrant English carpenters is trenching. In his book entitled English Historic Carpentry, Cecil A. Hewett describes a trench as ‘a square sectioned groove cut across the grain.’ The impetus for the focus on trenching came from a dissertation submitted to the University of Leicester where research of trenching was focused on studs in particular. However, trenching in the 17th century was implemented in braces, bridging-joists, purlins, rafters, and soffits as well. Though that is the case, not all 17th century structures trenched every timber mentioned. Equally, not every home built in early America used trenching at all. Similarly, the technique’s use, or non use, varied in England as well. A more thorough study of English carpentry across the countries needs to be done. This article provides a small glimpse into the uses of trenching on the different timbers mentioned and from where the technique may have originated. While carpenters who immigrated to America were not solely from England, the select houses studied for this work centered on English carpenters who were able to be connected to specific buildings in America, the carpenter’s place of origin, and their migratory path during their lifetime.

ENGLISH BEGINNINGS

Though the technique may have been used on earlier buildings, the archetypal of trenching is from the period between circa. A.D. 950 and 1050 used in The Church of St. Mary in Sompting, Sussex, England. In addition to being used in sole pieces in the soffit, trenching was also cut into the posts’ tops of the church spire to receive the principal-rafters, as well as in the flooring of the bell tower where the bridging-joists were trenched on their upper face to receive common joists. The technique continued in use for hundreds of years as seen in the trenching of the soffit to receive the faces of the collars in the high roof of the Angel Choir in the Lincoln Cathedral, Lincolnshire, built between 1256 and 1280. Trenching was also used on the outer faces of the rafters which received the diagonal braces in the roof construction above the North Transept of Westminster Abbey construction completed circa. 1269.

During Hewett’s exploration of the relationships between wall framing and first-floor mounting, he found that beginning from 1300 onward, wide-spread studs were being set more closely and studs were trenched obliquely across their external faces to accommodate the use of wind bracing. Trenching continued well into the 14th century, reaching into the beginning of the 15th century in Warwickshire buildings which used the technique mostly in purlins. What is most interesting is that trenching of building materials didn’t die out in the 15th century as can be seen in America’s colonial structures built in the 17th century by English carpenters.

EARLY AMERICAN USE OF TRENCHING

As English carpenters immigrated to America, the technique of trenching timber naturally found its way into the structures they built. By the mid-17th century the technique used on studs was morphing into a different approach, that of interrupted studs, presumably to save time and money. Despite this evolution, trenching of timbers is known to have been used as late as 1678 in America, with the earliest use attributed to the carpenter John Fawn, in the now razed dwelling of Samuel Symonds constructed about 1637. John Fawn was born in 1595, St. Olave Old Jewry, Kent, England. He had grown up in the center of London where he likely was exposed to many different techniques not only from England, but from surrounding countries. He may have also gleaned additional techniques from carpenters in Toppesfield, Essex, England where he resided just prior to emigrating. By the time John Fawn immigrated to Ipswich, Massachusetts in 1634, he was a master carpenter.

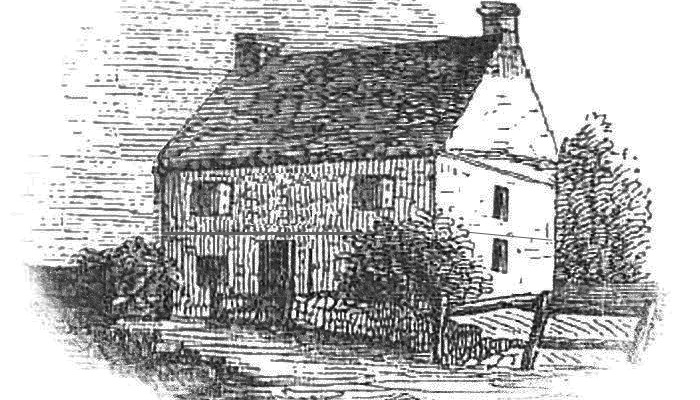

With the Symonds house having been razed, the earliest constructed building still standing today in America possessing trenched-studs is the Fairbanks house in Dedham, Massachusetts, completed circa. 1638 by Jonathan Fairbanks, born 1597 in Halifax, Yorkshire. Though Fairbanks is credited with its build, several carpenters had been brought into Dedham from outside the town during the early years of settlement. Thomas Fisher from Winston, Suffolk began building the meeting house in 1637. John Roper, a carpenter from New Buckenham, Norfolk arrived in 1637 and headed directly for Dedham. John Kingsbury, one of the original proprietors of Dedham, and a carpenter mason born in 1595, arrived from Boxford, Suffolk sometime before 1660. Lastly, John Elderkin, a carpenter from Lincolnshire, arrived in 1637 at the age of 21 years old. All of these early arriving carpenters may have been instrumental in the construction methods used on the Fairbanks house.

In 1982, Lowell Abbott Cummings, an authority on Massachusetts framed houses, stated that aside from the now demolished Symonds house, the Fairbanks House and Tuttle House were the only houses which possessed trenched timbers. The Tuttle House built 1671 in Ipswich, Massachusetts, 33 years after the Fairbanks house, possesses trenched braces to receive studs in the left-hand frame. However, at this time, a carpenter has not been attributed to the construction. While Cummings also suggested that there is no known English parallel, he conceded that with further endeavors examples may be found. Fifteen years later, in 1997, Hewett refers to the trench-jointed groundsills of the Songers timber-framed residential building located in Boxted, Essex which may be considered a prototype. Originally built as a one-storey, two-bay open hall, Songers’ ground sills are trench-jointed at right angles.

Though the method of trenching timber found its way into America from the Essex area of England beginning in about 1637, Cummings suggested that trenching of purlins and principle rafters were specifically a western practice. The only house using the technique known at this time to have been built by a carpenter born in western England is the Tristram Coffin house, built in 1678 in Newbury, Massachusetts by Tristram Coffin born in Bixton, Devonshire, England. Coffin used the technique in the purlins of his house which would confirm Cummings’s statement. However, Hewett considers the Foundry House in Coggeshall, Essex, England to be ‘absolutely’ prototypical of the Tristrim Coffin House. Whether he was taking the trenched timbers into consideration is unknown.

CONCLUSION

This article was but a small introduction into the trenching of timbers used in early American houses by immigrant English carpenters. Though this method has not been studied in-depth, it has long been scholars’ belief that an extensive study of the various techniques used in both America and England during the colonization of America would be of great value. It would assist in further comprehension of building methods, the time frame in which the method was used, when it went out of use, and which regions in England and America it is found. This would provide a window into the archaeology of those early structures, from where the technique originated, and how it made its way into the specific buildings in which it was used. Details learned from further study would also benefit social history and provide further insight into migration patterns. In addition, various organizations which host databases on documented structures, might find the inclusion of any discovery of the agency origins of artifactual features beneficial to its historical account and helpful to those studying buildings with those same features. Grants to further the study would be valuable.

REFERENCES

Anderson, R.C. (1995) The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England 1620-1633, Vol. I. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Anderson, R.C., Sanborn, Jr., G.F., and Sanborn, M.L. (eds.) (2001) The Great Migration: Immigrants to New England 1634-1635, Vol. II. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Arnold, L.J. (2018) ‘Connecting Early American Dwelling Artifactual Features to English Prototypes through Human Agency’, Masters dissertation, Historical Archaeology’, University of Leicester, Leicester, England.

Bacon, M. (1975) The Tristram Coffin House National Register of Historic Places. Washington: United Department of the Interior.

Banks, C.E. (1997) The Planters of the Commonwealth. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc.

Briggs, M.S. (1932) The Homes of the Pilgrim Fathers in England and America (1620-1685). London: Oxford University Press.

Carr, E.R. (2000) ‘Meaning (And) Materiality: Rethinking Contextual Analysis through Cellar-Set Houses’, Historical Archaeology, 34(4), pp. 32-45.

Coffin, J. (1845) A Sketch of the History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, from 1635 to 1845. Boston: Samuel G. Drake.

Cummings, A.L. (1982) The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725. Cambridge: The Belknap Press.

Deetz, J.F. (1978) ‘A Cognitive Historical Model for American Material Culture: 1620-1835’, in Schuyler, R.L. (ed.) Historical Archaeology: A guide to Substantive and Theoretical Contributions. Farmingdale: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc.

Deetz, J.F. (1996) In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life. New York: Anchor Books.

Farmer, J. (2006) A Genealogical Register of the First Settlers of New England. Westminster: Heritage Books, Inc.

Filby, P.W. (ed.) (2012) Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s. Farmington Hills: Gale Research.

Findley, L. (2005) Building Change: Architecture, Politics and Cultural Agency. London: Routledge.

Garvin, J.L. (2001) A Building History of Northern New England. Lebanon: University Press of New England.

Glassie, H. (2000) Vernacular Architecture. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Heintzelman, P. (1975) Fairbanks House National Register of Historic Places. Washington: United Department of the Interior.

Hewitt, C. A. (1970) ‘Some East Anglian Prototypes for Early Timber Houses in America,’ Post-Medieval Archaeology, 3, pp.100-121.

Hewitt, C. A.(1997) English Historic Carpentry. Fresno: Linden Publishing.

Hicks, D. and Horning, A. (2014) ‘Historical archaeology and buildings’, in Hicks, D. and Beaudry, M.C. (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Historical Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huber, G.D. (2006) ‘Abbott Lowell Cummings’ Prescience and Dates for First Period Houses of Massachusetts Bay Colony Using Dendrochronology,’ Material Culture, 38:2, p.50.

Index of Tree-Ring Dated Buildings in England National List, Vernacular Architecture Group 2021, located at: https://www.vag.org.uk/dendro-tables/england/date/1300-1349.pdf (accessed 25 June 2022).

Isham, N.M. (2007) Early American Homes. Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc.

Johnson, M. (1993) Housing Culture: Traditional Architecture in an English Landscape. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Johnson, M. (1997) ‘Vernacular Architecture: The Loss of Innocence’, Vernacular Architecture, 28(1), pp. 13-19.

Johnson, M. (2010) Archaeological Theory. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Johnson, M. (2014) English Houses 1300-1800. Abington: Routledge.

Kimball, S.F. (1922) Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

King, A. (2005) ‘Structure and Agency’ in Harrington, A. (ed.) Modern Social Theory An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leone, M.P. and Potter, Jr., P.B. (1988) ‘Issues in Historical Archaeology’, in Leone, M.P. and Potter, Jr., P.B. (eds.) The Recovery of Meaning: Historical Archaeology in the Eastern United States. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Mercer, E. (1975) English Vernacular Houses. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Mercer, E. (1997) ‘The Unfulfilled Wider Implications of Vernacular Architecture Studies’, Vernacular Architecture, 18(1) p.9-12.

Miles, D H, Worthington, M J, and Grady, A A, 2002 “Development of Standard Tree-Ring Chronologies for Dating Historic Structures in Eastern Massachusetts Phase II”, Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory unpublished report 2002/6. [Tuttle House]

Millar, D. (1915) ‘A Seventeenth Century New England House’, The Architectural Record, 38, pp. 349-361.

Morriss, R.K. (2004) The Archaeology of Buildings. Brimscombe Port Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

Orser, Jr., C.E. (2004) Historical Archaeology. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, Inc.

Oxford Tree-Ring Laboratory (2002b) Fairbanks House. Available at: http://www.dendrochronology.com/fhd-1.html (Accessed: 13 September 2018).

Oxford Tree-Ring Laboratory (2002d) Coffin House. Available at: https://www.dendrochronology.com/chn.html (Accessed: 25 January 2019).

Palfrey, J.G. (1892) History of New England, Volume 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

St. George, R.B. (1986) ‘“Set Thine House in Order” The Domestication of the Yeomanry in Seventeenth-Century New England’, in Upton, D. and Vlach, J.M. (eds.) Common Places Readings in American Vernacular Architecture. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Strong, R. (2009) ‘Two Seventeenth-Century Conversion Narratives from Ipswich, Massachusetts Bay Colony’, The New England Quarterly, 82(1), pp. 136-169.

Thompson, R. (2009) Mobility and Migration: East Anglian Founders of New England, 1629-1640. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Upton, D. (1981) ‘Ordinary Buildings: A Bibliographical Essay on American Vernacular Architecture’, American Studies International, 19(2), pp. 57-75.

Waters,T.F. (1905) Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Ipswich: The Ipswich Historical Society.

Weldon, M.E. (1978) The Kingsbury-Lord House. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Commission.

Wilkie, L.A. (2014) ‘Documentary Archaeology’, in Hicks, D. and Beaudry, M.C. (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Historical Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Worthington, E. (1827) The History of Dedham: From the Beginning of Its Settlement, in September 1635, to May 1827. Boston: Dutton and Wentworth.