{Buildings Archaeology Artifactual Feature Origins Part IV — Overhangs and Drops}

Introduction

As part of the series English Origins of Early American Building Techniques and their connections to English origins, we can see that the commonality among dwellings was not simply in the floor plan. This can be seen in the techniques of framing, which was considered “general” English mimicry. Framing would occasionally include an overhang, otherwise known as a jetty, a projection of a floor on storeys ascending above the ground floor, minimally increasing the floor areas. The variety of construction methods included the ‘hewn’ overhang, ‘bracketed’ overhang, ‘molded’ overhang and the ‘end’ overhang. Studying the origins of the feature provides a view into the evolution of construction methods and the migration of agency. Several examples exist in the US with minor variations such as chamfered overhangs in contrast to hewn overhangs, with additional details such as drops and/or decorative brackets. A couple of the best examples include the John Whipple House in Ipswich, Massachusetts, and the Deacon John Moore House in Windsor, Connecticut.

John Whipple (1677) — Chamfered overhang & decorative brackets

Ipswich, Essex County, Massachusetts

The John Whipple House was built in 1677, and though John Whipple, said to have immigrated from Bocking, England, is acknowledged as having built the earliest portion of the dwelling, his son, John Whipple, Jr., a carpenter, is accredited to have added the decorative hewn overhang in 1689. An additional notable feature are the decorative brackets under the overhang which were part of the 1689 addition. It is this overhang, built in hewn form, in which a comparison is drawn to the Grade II listed Candle Court in Reepham, Norfolk, England c.1565. Candle Court, now known as Cardinal’s Hat, is a two-bay, two-storey, heavily timbered dwelling with a hewn overhang. This type of overhang was also seen in the later c.1600 built Grade II listed Deal Tree Farm, Hook End, Blackmore in Essex, England, grossly altered in 1969. Though Reepham is nearly 90 miles away from Bocking, Blackmore is less than 24 miles and with its construction in the 16th century, it is possible that Whipple may have learned and been taken with the economic advantages of its hewn style since it used less timber to construct as opposed to the typical English framed style. A much earlier example is the Deacon John Moore House in Windsor, Connecticut which includes overhang drops.

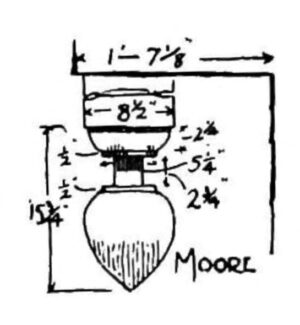

Deacon John Moore House (c. 1664) — Framed overhang & overhang drop

Windsor, Hartford County, Connecticut

The Deacon John Moore House is known for its framed overhang and overhang drops, which architectural historians Albert F. Brown and Norman Morrison Isham compare with several houses including the c.1723 Sheldon house in Deerfield, Massachusetts (demolished), the c.1650 John Clark house in Farmington, Connecticut (demolished), the 1683 Parson Capen House in Topsfield, Massachusetts, and the c.1660 Gleason house (considered the oldest house in Farmington, Connecticut). Architect J. Frederick Kelly points out that the gable overhang is secured by framing a second end girt outside of the first one, which is only seen in the Moore house and Stowe house in Milford, built c.1679-89. Knowing that Samuel Eells, a carpenter born in Dorchester, Massachusetts is accredited to having built the Stowe house, it is likely he also contributed to the Moore house overhang feature.

John Moore, being a woodworker, and contracted to work on town buildings such as the schoolhouse and meetinghouse between 1668 and 1676, more than likely had his hand the construction of his own home, but also utilized the expertise of other carpenters. Though John Moore was born in Southwold, Suffolk, England, before arriving in Windsor, Connecticut in 1638, he spent some time in Dorchester, England where he likely met Samuel Eells who immigrated to Connecticut after Moore. Besides his own skills and potentially those of Eells, John Stiles was considered the first master carpenter to settle Windsor, during which time he brought at least six apprentices. Born in Millbroke, Bedfordshire, England in 1595, Stiles first arrived from London in Windsor at the end of June 1635 after spending 10 days at the port of entry, Boston, Massachusetts. At the age of 40 Stiles was well skilled in carpentry, though it is possible that influence from skilled tradesmen in Boston may have provided some suggestions for construction in the unfamiliar territory. Stiles, along with his brother Thomas and at least two of the apprentices, Thomas Barber and George Chappel remained in Hartford during their lifetime. Though John Stiles and Thomas Barber were deceased by the time the Deacon John Moore house was built in 1664, it is possible that his apprentices, Thomas Stiles and George Chappel, may have been employed.

What This Teaches Us About Migration

Exploration of the agents’ movements provide some answers to and understanding of the implementation of specific features which followed a pattern along with any divergence away from the norm. While we may consider that migration took on a structuralist form, we learn that migration patterns are as varied as the immigrants themselves. For instance, though Connecticut was settled after Massachusetts, Isham and Brown consider the overhang a feature which was brought in through New Haven by immigrants “from Kent or of Yorkshire at Quinnipiac, or the settlers from Kent, Surrey, and Sussex who founded Guilford”. It subsequently found its way to Ipswich, Massachusetts through carpenters who migrated later to that town. This reveals a specific progression of migratory influence contrary to the standard migratory route of first arriving in Massachusetts and moving down to Connecticut. What we learn is that migration is not as linear as we may have once thought. While groups arrived on ships in specific ports, there was far greater varied movement in and around the country especially by craftsmen, creating a somewhat ambiguous picture of migration and the use of artifactual features in one place and not another.

A number of early American houses are devoid of English prototypes from scholars. This limits a comprehensive understanding of human agency and their behavior as it relates to the early American dwellings. While Kelly, Isham, and Brown point towards Hereford for overhang drops, they do not provide precise prototypes. This leaves the understanding of the Moore house artifactual features inconclusive without a deeper study of comparable buildings in America and prototypes in England. This article only touches on potential answers. Clearly further study is needed. To assist in a better understanding, several Colonial houses exhibiting the overhang artifactual features need further clarification which including:

- Buttolph-Williams (c.1692), Hartford, CT – 2nd storey hewn overhang and carved bracket

- John Clark House (before 1650), Farmington, Hartford, CT – bracketed overhand in gable

- John Hollister (c.1649), Glastonbury, Hartford, CT – end overhang and supporting corbels

- John Randall (c.1690), North Stonington, CT – overhang

- Joseph Walker (c.1690), Stratford, CT – hewn overhang

- Patterson House (c.1670) Hartford, CT – overhang (razed)

- Bernard Capen (1675), Milton, MA – decorative brackets in overhang gable

- Giddings-Burnham (c.1640), Ipswich, MA – overhang

- House of Seven Gables (1668), Salem, MA – overhang

- Robert Pierce (1683), Dorcester, MA – decorative brackets in overhang gables

- William Howard (c.1680), Ipswich, MA – molded overhang with carved brackets

- Codding House (c.1640), Newport, RI (razed) – overhang

References:

Brown, T.R. (1976) Deacon John Moore House National Register of Historic Places. Washington: United Department of the Interior.

Cummings, A.L. (1982) The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725. Cambridge: The Belknap Press.

Deetz, J.F. (1996) In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life. New York: Anchor Books.

Hewett, C.A. (1969) ‘Some East Anglian Prototypes for Early Timber Houses in America’, Post-Medieval Archaeology, 3, pp.100-121.

Hewett, C.A. (1997) English Historic Carpentry. Fresno: Linden Publishing.

Isham, N.M., and Brown, A.F. (1900) Early Connecticut Houses: An Historical and Architectural Study. Providence: Preston and Rounds Co.

Kelly, J.F. (1963) Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Kimball, S.F. (1922) Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Lane, J. (2018) Deacon John Moore, Community Craftsman. Available at: https://windsorhistoricalsociety.org/deacon-john-moore-community-craftsman/ (Accessed: 1 May 2019).

Leek, W.S. (c.1897) The 17th Century Deacon John Moore house, c.1897 photo [Online]. Available at: https://windsorhistoricalsociety.org/deacon-john-moore-community-craftsman/ (Accessed: 9 November 2018).

Millar, D. (1915) ‘A Seventeenth Century New England House’, The Architectural Record, 38, pp. 349-361.

Oxford Tree-Ring Laboratory (2002a) Whipple House. Available at: https://www.dendrochronology.com/alc6.html (Accessed: 8 November 2018).

Stiles, H.R. (1859) The History of Ancient Windsor, Connecticut. New York: Charles B. Norton.

Thompsen, E.B. (2008) John Whipple House photo [Online]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Whipple_House#/media/File:John_Whipple_House.jpg (Accessed: 30 April 2019).

Thompson, R. (2009) Mobility and Migration: East Anglian Founders of New England, 1629-1640. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

[Feature photo from

Note: The majority of the information in this article was taken from a dissertation submitted to University of Leicester in 2018 entitled Connecting early American dwelling artifactual features to English prototypes through human agency. To receive a copy of the complete dissertation contact Legacy Roots.