{Part 1 – Introduction}

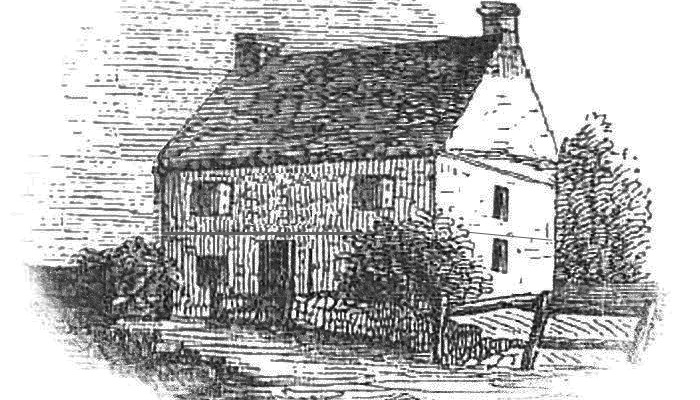

Anyone who has owned, cared for, or worked on a historic property can appreciate that the details of a structure’s origins get lost over time. We don’t often know or recall who designed a building, what techniques and materials were used, and even less so, who the individuals were who put the hammer to the nail or peg. Historically preserved and registered 17th century houses in America are often attributed to the owner. In some cases, the owner did in fact design and build the house, but there are many instances where that was not the case. Rather, in Colonial America it was master carpenters/builders who immigrated, sometimes specifically to assist in the building of houses in a newly settled area, who served as architect. While the professional title ‘architect’ did exist during that time, in early America it was more common to rely on master carpenters, who likely had architectural skills, to design and build dwellings. Those carpenters brought specific approaches and expertise from the regions in England where they learned their trade. Understanding the uniqueness of particular techniques used in different locations in Colonial America provides us with an uncommon view into the development of the early American landscape.

In an attempt to reveal this aspect of history, several historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, and even architectural historians studied physical structures and documents that were available during their lifetime over the past century. [See References for several publications touching on the subject.] As a historical buildings archaeologist, I was challenged by a dear colleague in 2018 to discover if it was possible to build on those early attempts. The quest was to bring clarity from where in England, and by whom, specific building artifactual features found their way into Colonial America construction in different regions. That quest turned into a successful dissertation on the subject. Unique features studied included trenched studs, widely spaced studs, hewn overhang, 2-story studs, bridging-joists, joint scarfs, vertical boarding, wall braces, bladed-scarf joints, end chimney plan, crossed summers, framed overhang and drops, and summer beams. For those who document, work on, own, or care for 17th century buildings, this is part of the structure’s history — the building’s archaeology.

Future posts in this series, ‘English Origins of Early American Building Techniques,’ will discuss the individual unique technique, the early American structure(s) which possess the feature, the carpenter, and the English prototype(s). My hope is that these articles will encourage us all to take a closer look at the bones of the building that is in our care. Doing so may provide a greater understanding of the building’s archaeological history and how we may better preserve it.

Constructive comments, additional information, and corrections are encouraged.

References:

Arnold, L.J. (2018) ‘Connecting Early American Dwelling Artifactual Features to English Prototypes through Human Agency’, Masters dissertation, Historical Archaeology’, University of Leicester, Leicester, England.

Briggs, M.S. (1932) The Homes of the Pilgrim Fathers in England and America. London: Oxford University Press.

Cummings, A.L. (1982) The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Hewett, C.A. (1980) English Historic Carpentry. Fresno: Linden Publishing.

Isham, N.M. (2007) Early American Houses. New York: Dover.

Johnson, M. (2014) English Houses 1300-1800. New York: Routledge.

Kelly, J.F. (1952) The Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

[Photo: Arnold, L.J. 2018 Lavenham, England.]